Lecture on Frankenstein, Chapters 10-11

T. A. Copeland

Generally when we ask why something happens in a work of fiction, what we mean is how does it arise out of the story, from the characters’ natures or decisions, or perhaps from forces set to work by the action of the plot, but we must also remember that authors have control of the events and may have their own reasons for inventing certain twists in the plot. The weather, for instance, is almost never caused by events in the plot or by the characters’ decisions, and Phil Green’s choosing to honeymoon at a hotel that has a policy of excluding Jews may be an accident from the characters’ point of view, Phil being new to the area, but is certainly no accident from the author’s point of view. Even though authors love to say that they simply leave the characters alone to interact, and they in effect write the story, we also have to remember that authors often choose to make things happen because they wish to contrive events. Agatha Christie might have left her characters to follow their own inclinations in Murder on the Orient Express, but if they chose to travel by dirigible rather than by rail, she would have had to call her novel Murder on the Hindenberg. Well, Mary Shelley has a definite plan in getting Victor away from people in Chapter10, and it isn’t solely to provide privacy for his interview with the creature.

She also must find a way for Victor get far enough past his loathing of the creature to hear its story; otherwise, we would not be able to learn the story, for the author has deliberately avoided the omniscient point of view, like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s, for instance. Everything in this novel must reach our ears from the mouth or the pen on one or another of the characters in the story.

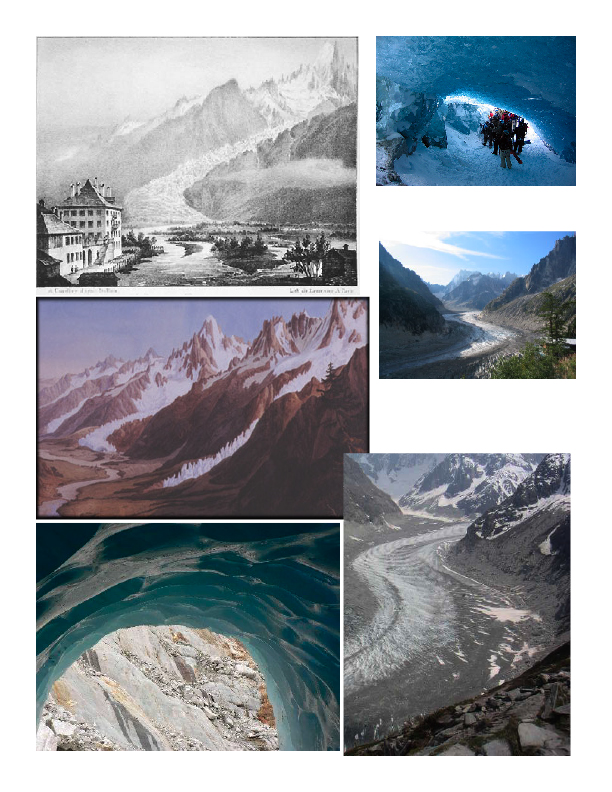

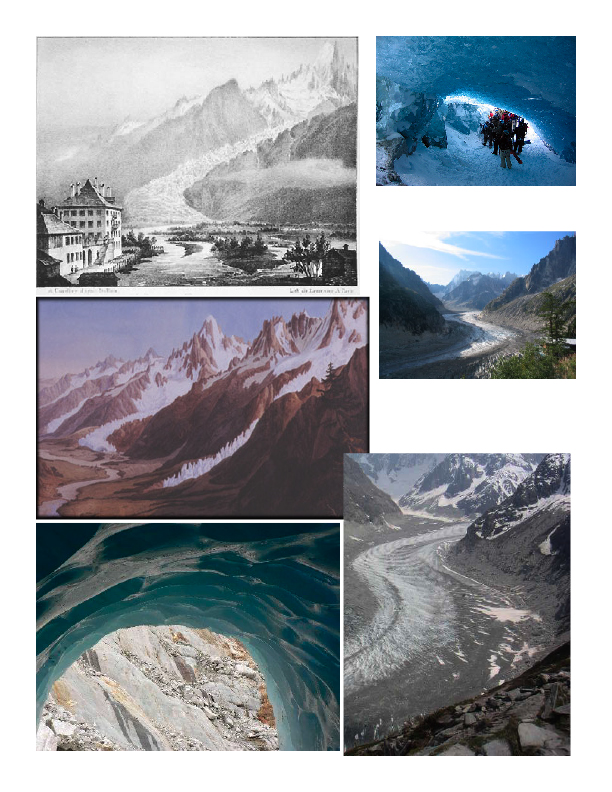

So Shelley must put Victor in the proper frame of mind to converse with the creature, and that, I submit, is why she causes him to visit the glacier at Chamounix: “These sublime and magnificent scenes,” he says, “afforded me the greatest consolation that I was capable of receiving. They elevated me from all littleness of feeling, and although they did not remove my grief, they subdued and tranquillized it.” Unhappy people, especially addicts and dying persons, often testify that finding a way to escape from being the center of their own sick universe relieves them of a large part of their misery simply because it is dwarfed beside things of greater moment. I recommend Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” as the supreme literary treatment of this phenomenon, or you could just go to an AA meeting and listen to a “lead” by a recovering alcoholic.

In any case, the sublime majesty of the tremendous landscape around the glacier works to bring Victor’s feelings within his control. However, the author also takes advantage of the new setting for symbolic purposes. I believe that, from the very beginning of this project, she was conscious that her novel was not simply about creating life. It was about the possibility of mankind’s sharing this planet with a superhuman race. The landscape of Switzerland makes such thoughts spring spontaneously into the mind, for it is on such a grand scale that human habitations appear like so many ant hills; the terrain is suited to beings much larger than we are, and stronger, more nimble, and better able to bear the cold. The creature demonstrates that he has these qualifications, so when he promises that he and his descendants will keep to the wilds and not molest mankind, we know that they can do it. I think that Shelley begins to make us think along these lines in the very first paragraph of Chapter 10, where she describes the landscape with some gigantic and superhuman personifications:

The abrupt sides of vast mountains were before me; the icy wall of the glacier overhung me; a few shattered pines were scattered around; and the solemn silence of this glorious presence-chamber of imperial nature was broken only by the brawling waves or the fall of some vast fragment, the thunder sound of the avalanche or the cracking, reverberated along the mountains, of the accumulated ice, which, through the silent working of immutable laws, was ever and anon rent and torn, as if it had been but a plaything in their hands. [Red=personification, bold=rhyme, italics=alliteration. The rhyme and alliteration simply decorate the passage, calling attention to it as would a yellow highlighter.]

This is, as it were, the secret dwelling place of nature and her laws, and Victor has already found it in his lab experiments, but he is now here in person. Back in Ingolstadt he tapped into the immutable laws of nature, and these same laws are shown here as the children of Mother Nature, portrayed as an empress who sits here enshrined, surrounded by these children that tear up monstrous slabs of ice as if it were styrofoam. Victor has added to this empress’s brood by creating a being who is at home here and who seems to come on cue the moment Victor addresses the spirits or daemons that haunt this place:

“Wandering spirits, if indeed ye wander, and do not rest in your narrow beds, allow me this faint happiness, or take me, as your companion, away from the joys of life.”

As I said this I suddenly beheld the figure of a man [which comes, one might say, like the answer to his prayer], at some distance, advancing towards me with superhuman speed. He bounded over the crevices in the ice, among which I had walked with caution; his stature, also, as he approached, seemed to exceed that of man.

At this point, Victor’s earlier rage and detestation return with a vengeance, and his new-found tranquility is banished, along with the humility and sense of his own smallness which he just now acquired from the landscape. The author takes some pains to make us aware that this is a kind of back-sliding, not a desirable state of mind, for first she makes us see that Victor is unable to pay attention to the complexity of the creature’s facial expressions, although we can see them and wonder about them: “He approached; his countenance bespoke bitter anguish, combined with disdain and malignity, while its [that it, the countenance’s] unearthly ugliness rendered it almost too horrible for human eyes. . . .” We are being made curious about the creature, with its apparent suffering, counterbalanced by a combination of pride and ill will, and since Victor was at the time not curious but only repelled and angry, we distance ourselves a little from him. We continue to do so when he addresses this superman with a pride that makes him sound absurd:

"Devil," I exclaimed, "do you dare approach me? And do not you fear the fierce vengeance of my arm wreaked on your miserable head? Begone, vile insect! Or rather, stay, that I may trample you to dust!

How tall is Victor? Maybe six feet? And this being is eight feet tall. Dwarf threatens giant: it’s a classic comedic situation. The distancing continues as the creature does not imitate Victor’s wild rhetoric but speaks in measured tones, reasoning mildly but not timidly with his maker. A reader who remembers Adam’s first conversation with God in Paradise Lost, where God gives him a hard time about his desire for a mate—but just to see how well his new creature can argue—will see here that the creature, who (as we will later learn) has also read Milton’s epic poem and is now busy leading up to the same demand Adam made, has learned the big lesson well: Keep on task, and don’t lose your cool. Victor, however, hasn’t learned that lesson and continues blustering and threatening in vain, until finally, like a maddened bull, he charges across the ice, and the creature dodges him with the casual ease of a toreador:

My rage was without bounds; I sprang on him, impelled by all the feelings which can arm one being against the existence of another.

He easily eluded me and said, “Be calm! I entreat you to hear me before you give vent to your hatred on my devoted head.”

“Devoted head,” by the way, means a head “consigned to evil, doomed,” but the word devoted also suggests that the creature may be thinking of his duty to his maker, as when one speaks of a “devoted” servant, especially since he goes on to promise to

. . . be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample [notice how the creature quotes Victor—trample] upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

Well, that promise sounds a little naïve, but the creature is certainly not the mindless beast of rage and destruction that we were expecting. If only it didn’t look so horrible, maybe even Victor could be patient enough to let us learn more. We WANT to learn more about the creature now, don’t we?—and I think we are getting a bit annoyed with Victor’s stupid rage. At least I am. In any case, the creature understands that the real problem is its ugliness. Let me quote yet another passage, in which Victor’s words suggest a dawning suspicion that he may not have been fair to his creature. The creature seems to hear this too, and it shows him how to take the next step:

“You have made me wretched beyond expression [says Victor]. You have left me no power to consider whether I am just to you or not. Begone! Relieve me from the sight of your detested form.”

“Thus I relieve thee, my creator,” he said, and placed his hated hands before my eyes. . . .

This, of course, doesn’t make a hit with Victor; it’s a form of mockery, after all, but the message is clearly that he has only to close or avert his eyes and his anger will dissipate. It takes a few more nudges, but eventually Victor decides to give the creature a hearing:

I was partly urged by curiosity, and compassion confirmed my resolution. I had hitherto supposed him to be the murderer of my brother, and I eagerly sought a confirmation or denial of this opinion. For the first time, also, I felt what the duties of a creator towards his creature were, and that I ought to render him happy before I complained of his wickedness. These motives urged me to comply with his demand.

We have never before heard and will never again hear Victor admit that he may have owed his creature any support or nourishment after bringing it into the world, but the fact that he does this once acknowledge his undischarged debt makes clear that he is far from unaware of his fault, however much he may strive to blind himself to it by pretending that his real fault was in creating it in the first place.

And so off they go to a hut such as the Swiss provide throughout the mountains for the use of climbers overtaken by snowstorms. Here, in Chapter 11, the creature describes how his consciousness began to register the outside world. This is the beginning of his education, and, following the theories of John Locke, a seventeenth-century philosopher, it begins at the level of sensation and consists largely of separating and sorting out various kinds of information. Computers, by the way, can do almost anything, but as yet I do not believe that they can take a pure jumble and arrange it into a sensible kind of order unless they are fed with the criteria of that arrangement; to invent or discover order takes imagination, which they lack. But people can do this, so for two whole pages we keep seeing the words distinguish and distinct over and over again, and this seems to be the beginning of learning in Shelley’s view:

Pg. 1: All the events of that period appear confused and indistinct. A strange multiplicity of sensations seized me, and I saw, felt, heard, and smelt at the same time; and it was, indeed, a long time before I learned to distinguish between the operations of my various senses. By degrees, I remember, a stronger light pressed upon my nerves, so that I was obliged to shut my eyes. Darkness then came over me. . . .

Pg. 3: No distinct ideas occupied my mind; all was confused. I felt light, and hunger, and thirst, and darkness [How does one “feel” light and darkness? This is synesthesia, as when Adam, also recalling his earliest sensations, says, “With fragrance and with joy my heart o’erflowed”—experience soup]; innumerable sounds rang in my ears, and on all sides various scents saluted me; the only object that I could distinguish was the bright moon, and I fixed my eyes on that with pleasure.

Pg. 5: My sensations had by this time become distinct, and my mind received every day additional ideas. My eyes became accustomed to the light and to perceive objects in their right forms; I distinguished the insect from the herb, and by degrees, one herb from another. I found that the sparrow uttered none but harsh notes, whilst those of the blackbird and thrush were sweet and enticing.

Pg. 6: One day, when I was oppressed by cold, I found a fire which had been left by some wandering beggars, and was overcome with delight at the warmth I experienced from it. In my joy I thrust my hand into the live embers, but quickly drew it out again with a cry of pain. How strange, I thought, that the same cause should produce such opposite effects! [Cause and effect have been distinguished.]

Of the many lessons the creature learns, the most painful one is how utterly distinct he is from human beings. That separation, which is enforced upon him by people who treat him with hostility, he does not yet understand, for he has never yet seen himself and doesn’t know why they attack him or flee when they see him, and it must seem all the more mystifying because in spite of their behavior he senses his inner kinship to them, and they draw his interest and his love. When he begins to study one family from a hiding place, we might possibly be offended by his acting like a peeping Tom, but since he admires these people and feels sorry for them once he learns that they are not happy—and even does chores for them when they are asleep—we do not find his actions offensive.

By the end of Chapter 11, I think I can speak for all readers when I say that we can scarcely remember the horror that we felt before, when Victor ran from the creature, or the rage that we shared with him when we thought of his strangling a helpless little boy. Can this be the same being we saw in the thunderstorm? Shelley has hooked us, and although we have the creature’s own assurance that he is indeed a “fiend” by the time he begins this conversation with Victor, we can be certain that he was by no means a fiend at the time of his creation or even after several unhappy encounters with cruel human beings. Whatever else we may learn later on, this much we know now: Victor did not create a monster, as he is so often in the habit of saying. If the creature is a monster now, Victor may indeed be responsible for it, as he is also in the habit of saying, but the reason can have nothing to do with any mistakes he made in the lab or even with his having dared to play God in creating life. There was absolutely nothing wrong with this creature to begin with except for its ugly face. There is still nothing wrong with it at this point in its tale. It was innocent, sensitive, and benevolent. To blame Victor for bringing goodness into the world seems to me irresponsible, unreasonable, even perverse.

Notes

Synesthesia: A psychological term for the interconnection among different senses. From a purely literary point of view, this quotation illustrates zeugma, the mismatch between grammatically parallel items, one of which works well in the context while the other does not. One might call the quotation a paradox that appears at first to be zeugma until one recognizes the synesthetic dimension of the words, which resolves the conflict. Return to text.