Lecture on Frankenstein, Chapters 6-7

T. A. Copeland

Chapters

6 and 7 form a contrasting pair. Each begins with a letter from home, from a family member whom Victor

has neglected all the while he has been a student. Each letter leads him out of his convalescence and toward

home. But against this background

of similarity, the horrible contrast between the two messages stands out

stark and grim, and the cause of this sad change is, as we eventually learn,

the creature’s criminal activity, for while Victor has been gradually coming

out of the mind-numbing stupor of his illness, the creature has been gradually

growing conscious of the world around him and adapting to it. You will soon read a detailed

account of what has happened to him, but for the time being suffice it to say

that at about the same time that Victor can say of himself, in the third

paragraph from the end of Chapter 6, “I became the same happy creature who, a few years ago, loved and beloved by all, had no sorrow or care”—at

about this same time, I say, the other creature, the one he has brought

into the world, has become a thing of sorrow and bitterness, its dearest hopes

dashed again and again and its good deeds repaid with insults, cruel

name-calling, and violence, until at last it has sought out its maker—for

redress and, as luck will have it, for revenge. It has learned his identity and the nature of its own birth,

and it blames him for abandoning it to a life of misery in a hostile world. An innate sense of justice, nourished

by reading books, has led the creature to demand of its parent some belated

aid, but by a fatal mischance it has blundered into committing a crime against

him. This accident, it has accepted as its deed, for it finds pleasure in the thought that it has harmed its maker, and, yielding to the dark side of its nature, it has committed a second crime, this one in cold blood and with malice aforethought. Meanwhile, Victor is blissfully unaware of its activities

and is indifferent to whether it lives still or has died. Nothing could be more ironic than the

last sentence of Chapter 6: “My own spirits were high, and I bounded along with

feelings of unbridled joy and hilarity.” Even now, at home the letter awaits him to reveal that his little brother has been murdered. The next chapter’s purpose is to bring Victor out of his

fool’s paradise and introduce him to the consequences of his irresponsibility.

Let’s turn now to the content of the letters, since they set the stage for what awaits Victor at home. From Elizabeth’s letter, at the beginning of Chapter 6, we learn much of value to the plot and also to the interpretation of the novel. Much of this letter’s content, of course, is really for our benefit, since we know very little of the household of the Frankensteins, but the information is introduced plausibly enough as Elizabeth’s effort to help Victor recover. She knows that his mind has been impaired by his illness, so she assumes that his memory may be imperfect. That is why she reminds him of who Justine Moritz is. Does anyone remember why Justine first came to live with the Frankensteins? These details are not just extra bits and pieces. Justine is a significant character—for two reasons: She is the creature’s second victim, and her story in certain ways resembles that of the creature. Shelley uses this parallel to precondition us to react to the scene in the following chapter, Chapter 7, where Victor catches sight of his creature.

Let’s look at the history of Justine. She was “through a strange perversity” rejected by her mother, who “could not endure her.” Remind you of anyone? But Mme. Moritz was persuaded that the deaths of her other children might be a judgment of God on her for rejecting Justine, so she asked her to come home. Still, though, the two of them could not be firmly reconciled. What did the mother accuse her daughter of? Killing her siblings. You see, she could not bear the thought that her own mistreatment of Justine might be to blame for her children’s deaths, the rather goofy story her priest was encouraging her to believe, as if God would kill innocent children to punish their mother, and so she projected her own guilt onto her daughter. Justine was to blame, not she. We’ll come back to Mme. Moritz later when Victor accuses his creature of killing little William.

First, though, we learn in Chapter 6 more facts that fill out Victor’s story so that it may be held side by side with the creature’s for comparison: Victor rather idly takes up the study of Oriental languages, even though he has earlier told us that language study never much interested him. He does it now just for a change and to

be a fellow-learner with Henry. When later we learn of the creature’s activities during the two years of

Victor’s sickness and convalescence, we find that he too has become a student

of language and that he too learned alongside another student—one (it is

true) that did not know of his existence, but, through a pitiful self-deception,

the creature pretended that she was his friend. This particular parallel turns out to be a kind of mirror

image—with a reversal—for as Victor, whose native language is

French, learns Arabic with Henry, the creature learns French with an

Arab. These parallels between

the creature’s experiences and those of Victor and Justine are not yet visible

to a first-time reader of the novel, but I am telling you about them so that

you will not suppose that the long story about Justine’s past and the somewhat

tedious account of Victor’s further schooling are just fluff. What we can eventually see, once the

creature’s story is told, is that while Mme Moritz’s dislike of her daughter certainly

caused the girl suffering, it was nothing when compared to the creature’s

suffering as a result of being abandoned by his maker, and while Victor is

enjoying the brotherly love of his best friend, which completes his recovery

from his breakdown, the creature is suffering from an intolerable loneliness,

the misery of which is exceeded only by his rare and tragic encounters with

human beings.

Turn

the page to Chapter 7 and you find out what “Paradise Lost” means. This is the world after the

fall—not the fall of mankind but the fall of the new man, the

creature. And at this point in the

novel I am glad you are first-time readers, for when you studied these chapters,

you did not know for certain that the creature had killed little William. You may now be ready to believe it,

especially since I tell you that he did it, but you did not then know

it, and neither did Victor. Victor doesn’t know it even at second hand; nobody told him. I hope that as a first-time reader you

found it a little weird that he was so certain the creature was a murderer. The fact that we later

learn from the creature’s own lips how and why he committed these outrageous

crimes tends to make us forget later on any misgivings we may have had here about Victor’s incautious reasoning, but it would really be hard for anyone

reading carefully not to have such misgivings, in view of Mrs. Moritz’s

unjustifiable suspicion that Justine killed her brothers and sister. Shelley, I think, wants us to see that,

like Justine’s mother, Victor is thinking with his emotions rather than with

his head, and therefore he is no trustworthy guide to interpreting his life

story. Let’s take a close look at

his first encounter with the creature since he saw it awake in his laboratory.

I’m going to play for you an adaptation of that scene. It begins about a page or a page and a half after the letter from Victor’s father at the start of Chapter 7. The paragraph begins, “It was completely dark” (p. 62). This adaptation, by Christopher Casson, replaces Victor as narrator with a female voice, presumably the author’s, and of course therefore changes the first-person pronouns to third-person. There are also many abridgements and some very nice sound effects which partially compensate for the words lost. See if you can follow it.

[Click here to hear the Christopher Casson adaptation.]

But that’s just to get you interested. Now I want you to hear the same passage read with fewer cuts by a truly accomplished actor, James Mason, with just a suggestion of a Swiss accent. He does, however, omit entirely the paragraph beginning “I quitted my seat and walked on” along with the sentence before it.

[Click here to hear the reading by James Mason.]

Now, this is the passage I want to look at critically. Victor is consumed with an irrational hatred of his creature, who became his “enemy,” at least in his own mind, on the very night of its creation and who is now “the filthy demon to whom I had given life”—reviled before Victor has even the suspicion that he killed William. Why on earth does Victor hate this creature so violently? Not for any rational reason. Yet the very first thought he has upon seeing him on this rainy evening is “Could he be (I shuddered at the conception) the murderer of my brother?” It might be fun to psychoanalyze Victor. I feel inclined to see in him some obscure guilt for not providing for his creature after its creation, and this guilt is so uncomfortable that he has projected it upon the creature. The parallel to Mme. Moritz is not perfect, of course. For one thing, the creature really did do the murders, while Justine was innocent, and for another, Victor does not deny all blame. However, he prefers to blame himself for creating the creature, not for being a bad parent to it. That guilt would be too hard to bear since he himself had such exemplary parents. However, we really need not bother with psychoanalysis right now because we have enough to keep us busy just dealing with the words on the page. Consider Victor’s next statement: “No sooner did that idea cross my imagination than I became convinced of its truth.” This is a scientist speaking, and he is leaping to a conclusion. Forget the fact that it is a true conclusion; leaping like this isn’t the way scientists reach conclusions. He goes on to say, “Nothing in human shape could have destroyed that fair child. He was the murderer! I could not doubt it.” Well, Victor surely doesn’t subscribe to a 20th -or 21st-century newspaper, does he? He never heard of the Lindbergh baby or JonBenét Ramsey, of course, so it had to be the bogeyman that did it, right? This isn’t rational thought we are witnessing. And get the next sentence: “The mere presence of the idea was an irresistible proof of the fact.” What, are we back in 17th-century Salem at the witch trials? Or is this some perverse application of that famous proof that God exists simply because we have an idea of God in our minds, and one of the attributes of this idea of God is that God exists? How is one to respond to this sort of reasoning?

My point is that when you find critics busily gathering quotations from Victor Frankenstein to illustrate their interpretations of his story, please remember that Victor is—if not insane—then at least unstable and unreliable. The critics also have lots of fun quoting words out of context and with altered spellings. Consider what Victor says in the next paragraph but one, the one beginning “No one can conceive”: He says that he “considered the being whom I had cast among mankind and endowed with the will and power to effect purposes of horror, such as the deed which he had now done [how does he know that?], nearly in the light of my own vampire, my own spirit, let loose from the grave and forced to destroy all that was dear to me.” My, oh, my, how the critics love that one! The creature is some kind of alter ego, a Mr. Hyde to Victor’s Dr. Jekyll, a doppelganger or fiendish avatar. But you have to forgive them, for even if the creature isn’t really Frankenstein’s evil twin, Frankenstein does gradually remake himself in the image of his creature, speaking of himself as an “evil spirit” and referring to “the fiend that lurked in my heart,” just as the creature refers to “the fiend within me.” I accept this analogy myself, but only as long as it is seen as a poetic fiction, as it is, I think, in Victor’s mind.

There’s one more word, though, that deserves some examination before we leave this passage. Victor calls the creature “the filthy demon to whom I had given life.” Shelley spells that noun “daemon.” The other spelling, “demon,” did exist in her day and meant a fiend of hell, and although this word, “daemon,” could be used in that sense too, in its original sense and spelling, “daemon” was a Latin word which signified a spirit that inhabits and protects a particular locality like a spring or a pool or a tree. This, too, seems to me like a poetic fancy, probably Shelley’s, though, not Victor’s. Victor clearly means “fiend,” but Shelley seems to be suggesting by her spelling that this creature belongs in parts of the world in which human beings do not dwell and therefore that this new race might co-exist with humankind without threatening our survival. We have already seen the creature climb the perpendicular and even overhanging side of Mont Salêve, and we will soon see him on a glacier, relaxed and at home where Victor has to pick his way with care. And on both of these occasions, the creature seems to appear almost magically as if summoned by Victor’s voice addressing wandering spirits. This is the way you would invoke the daemon of a pool in ancient days, although you would of course have to use its real name. This, by the way, resembles an old tradition in British folklore: that if you utter the name of a dead person or a fairy or an elf, there is a real chance that it will come at your call; it’s a kind of word magic, and it is behind our traditions surrounding funerals. We are never to utter the dead person’s name; he is simply “the departed” or “the deceased.” And we all wear black so that in case the ghost is accidentally summoned and has a grudge against one of us, he will have a hard time telling one from another. The analogy isn’t perfect, but there is enough similarity to call attention to that scene you just read where Victor no sooner cries out to William’s ghost than he catches sight of the creature. If this happened only once, we would call it a coincidence, and it may well be a coincidence in the world Victor inhabits, the world of literature, but we inhabit the world of the creators of literature, where nothing happens by chance, and when it happens a second time, in Chapter 10, well, it is clearly intended by the author for some purpose.

I’d like to take you to Chapter 10 for a moment, partly as a preview of coming attractions but mainly to demonstrate how this idea of the creature as an inhabitant of a superhuman landscape came to me. I owe it to the process by which Caedmon Records pares down a complete novel to fit onto two sides of a long-play record. The cuts they made placed side by side these two summonings of the creature out of the landscape. I might have noticed the similarity without hearing the record, but I like to give credit where credit is due. Please follow the text with me, if for no other reason than to warn you that unless they say “unabridged,” you really have no idea how far the producers have strayed from the actual text. Fortunately, the Caedmon staff do not insert words; they work exclusively with the author’s own language, but they do make severe cuts.

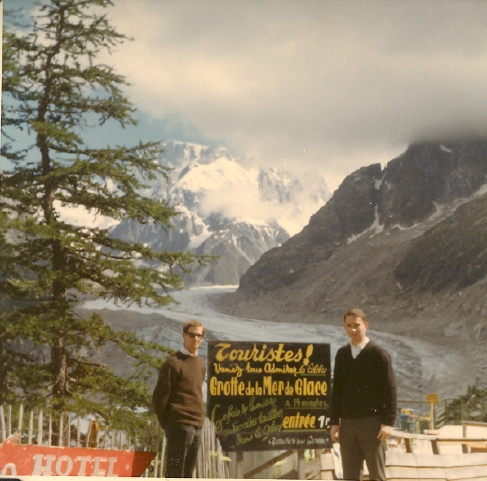

Please keep your finger in the text where we have been reading: “No one can conceive the anguish . . .” (p. 63), but then turn to chapter 10 and turn to p. 85, where you will find the quotation of verse. Just below that you will see a sentence that reads, “It was nearly noon when I arrived at the top of the ascent.” Mason will pick up here with the last four words of this sentence: “top of the ascent,” which thus completes the sentence begun on p. 63. Glance down a few lines to find, “I descended upon the glacier” and put a mark there. The reader, James Mason, will skip the next nine lines or so and pick up again, later in the same paragraph, with “The sea, or rather the vast river of ice,” referring to the “Mer de Glace” which you can walk out on if you visit Chamounix. Mark this place too.

Turn back now to where you placed your finger to mark the place. As I play the next bit for you, remember that you have seen this happen before.

[Click here to hear the rest of the selection.]

|

|

|

|

Keep your eye peeled for other occasions when Victor addresses spirits or when mention is made of spirits that preside over certain localities. At such moments the creature is generally not far off and sometimes makes his presence known. These rather fanciful passages, which began on the night of the creature’s birth—when Victor thought of its possibly waiting for him like a “specter” on his return to his apartment with Henry—have various serious purposes. The first was to make us suspect Victor’s sanity, for he had previously been free of supernatural terrors, but we see him grow increasingly fixated upon spirits as his story proceeds. Then, when the creature seems to reply to Victor when he addresses wandering spirits in landscapes hostile to man, we may find ourselves wondering if the creature is not in some strange fashion something like a daemon or tutelary spirit, who has found a home where human beings cannot live and from which they will perhaps not drive him away. This concept is worth pondering, for the most serious moral question Victor will face is whether humanity can co-exist with the new race of supermen that he has created. I suggest that by making the creature, like an abominable snowman, gravitate to cold and forbidding habitats, the author is inviting us to think that some equitable détente between the races might be achieved.