Lecture on Frankenstein, Chapters 8-9

T. A. Copeland

Chapter 8 is designed to make us aware of how easy it is to condemn without understanding. As you know, Victor will meet his creature face to face in Chapter 10, and the creature will beg and threaten him not to refuse him aid without first listening to the story of his difficult first two years of life. Up until now, most first-time readers probably accept uncritically Victor’s assumption that the creature was flawed from the start and that he should never have given it life, but it is now time to begin reassessing these beliefs. As of Chapter 8, we know for certain absolutely nothing to incriminate the creature except that Victor saw it near where the child was killed about a week earlier. This, we know, is the weakest imaginable circumstantial evidence, but Victor has already convicted the creature in his heart. The trial and execution of Justine are the author’s method of making us conscious of the injustice of basing judgments on this kind of evidence, but Victor himself cannot see this lesson; in fact, the injustice done to Justine will make it still harder for him to open his mind far enough to give the creature a hearing because he sees Justine’s indictment as well as his brother’s murder as the creature’s doing. Eventually, of course, we do discover that the creature is guilty, but that is because he confesses, and on that evidence we may base our judgment. But the point is that neither we nor Victor yet has that evidence, and it is not fair or wise to make any judgment until all the facts are in. Almost miraculously, Victor will suspend judgment in hopes of hearing the creature confess, and my belief is that the author is most anxious for us also to suspend judgment after seeing how human institutions can do immeasurable harm to innocence when people judge by appearances.

I have pointed out already many occasions when Victor and others have based judgments wholly or partially on appearance. Elizabeth’s beauty was an asset that helped to rescue her from a desperate situation; the same might perhaps be said of Caroline. On the other hand, Professor Krempe’s “little, squat” figure, “repulsive countenance,” and “gruff voice” prejudiced Victor against him, whereas the moment he saw the erect posture and heard the sweet voice of Professor Waldman, his mind became impressionable. And when he saw his creature move, its ugliness seems to have blinded him to his own tremendous achievement in endowing it with life. Certainly it prevented him from thinking clearly about what ought to be done next, and therefore if we want to spare Victor our censure, we can blame ugliness for allowing the creature to wander away from the one place in the world where he should—and indeed, might eventually—have been treated with kindness. When we hear the creature’s story, we will see time after time how his ugliness fills people with fear and rage and deprives them of the power of rational thought. Well, watch now, for much the same thing happens to poor Justine.

She is well aware of how much appearances matter and of how she damaged her case by her confused responses to questions before her arrest, so she does her best to rectify this. Paragraph 2: “The appearance of Justine was calm. . . . She appeared confident in innocence and did not tremble, although gazed on and execrated by thousands, for all the kindness which her beauty might otherwise have excited was obliterated in the minds of the spectators by the imagination of the enormity she was supposed to have committed.” The problem, of course, is that the courtroom is filled with people who think they know how to see through Justine’s appearance of innocence and courage, but they are still guilty of judging by appearance; they have prejudged her. On what basis? Is it circumstantial evidence? No, that has not as yet been presented in court. The mere accusation has been enough to prejudice the onlookers, and when Elizabeth acts as a character witness, her efforts backfire because the audience start with the assumption of Justine’s guilt and then, seeing Elizabeth’s unselfish love for her, they blame Justine for ingratitude as well.

Nor are the judges any better—and the persecution does not end in the courtroom. It follows her even to the cell where she awaits execution. What does Justine say about her confessor? There were not a lot of Roman Catholics in Geneva in the late eighteenth century; Geneva was the home of Calvinism, so Shelley must have chosen for Justine to be a Catholic for some literary purpose, and that purpose seems pretty obviously to be so that she could have a confessor, one who, convinced like everyone else by flimsy evidence—that is, by appearances—would hound her and threaten her until she confessed what she’d never done. I asked a Catholic priest online whether lying during the sacrament of Confession is a sin, and he said it’s a mortal sin; you burn in hellfire forever for it. So after having her body consigned to death, Justine next has her soul consigned to everlasting damnation by being bullied into committing a mortal sin. How’s that for an indictment of two human institutions, both dedicated to achieving justice? But Shelley is not yet quite finished with her exposé of how human institutions fail the innocent: How does Victor find out that Justine has confessed to the crime? How does anyone find out? What is implied? Clearly the priest broke the seal of the confessional, probably the most sacred of all solemn vows taken by priests: not to reveal to a living soul anything revealed in a confession, not even to save a life.

Another priest I consulted, an Orthodox priest, said that this confessor had abused his authority and betrayed the trust Justine had in him, trust that presumably he had nurtured over time, since a penitent must trust her confessor if she is to confess freely. Even to doubt her at this point, he said, is a betrayal, and as for threatening to withhold absolution as a means of extorting the confession that he wants to hear, it’s practically unheard of and could be justified only in very rare cases where the priest had special knowledge of the penitent’s soul. “He’s skating on very thin ice there,” he said, but when the confessor then breaks the seal of the confessional, well, there is no question who has sinned the greater sin. My friend thought Justine had a good chance in the next life, but the priest didn’t—just in case you wondered what the “professionals” think.

Digression on the Kenneth Branagh movie Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: How does Justine die in the movie? She’s hustled off to be hanged from a church steeple—a nice little bit of Hollywood shorthand, it’s quick, pathetic, but very diluted. It’s certainly unsettling to see a red-faced mob lynch a pretty girl without giving her a hearing, but it’s absolutely appalling to see her killed by the legal system and damned by the religious establishment with all the appearance of due process. Shelley’s portrait of humanity is withering, ten times more scathing than the movie. After this, we ought to be humbled, even ashamed of being human, and ready to hear what kind of case this new being can make for himself.

It might also be worth mentioning that Shelley the artist has not been asleep while Shelley the social critic has been at work. Here’s how Chapter 8 looks from an artistic point of view. After seeing Elizabeth in Chapter 7 agonizing over her own imaginary guilt (that she killed William by letting him wear the locket) and confessing it all over the place, even though she is completely innocent, we then turn in Chapter 8 to view balanced opposites composed of these same elements but differently distributed: Victor feels guilty but dares not confess, whereas Justine knows herself innocent but is forced to confess: balanced and opposite frustrations. Why, by the way, doesn’t Victor tell what he knows?

Anyway, he bears his supposed guilt with him into Chapter 9, where he turns away from his family. Now, I told you before to expect this kind of behavior from him. It’s just the kind of thing Romantic heroes are famous for: moping around, consumed with nameless guilts which remove them from those they love best because they can’t share their secret sorrows: “I shunned the face of man; all sound of joy or complacency was torture to me; solitude was my only consolation—deep, dark, deathlike solitude” (p. 77). Romantics are always excessive in every emotion, and Shelley makes us feel how wide is the gulf separating Victor from others by how his old father is characterized. Old Alphonse is not only innocent in mind, which makes him unable to understand the nature and magnitude of Victor’s grief (complicated as it is by his feeling of guilt); he also belongs to the Age of Reason, the early eighteenth century. Listen to his very unromantic, temperate, rational voice: “‘Do you think, Victor,’ said he, ‘that I do not suffer also? No one could love a child more than I loved your brother’—tears came into his eyes as he spoke—‘but is it not a duty to the survivors that we should refrain from augmenting their unhappiness by an appearance of immoderate grief? It is also a duty owed to yourself, for excessive sorrow prevents improvement or enjoyment, or even the discharge of daily usefulness, without which no man is fit for society’” (p. 78). But of course, Victor, good Romantic that he is, finds it necessary to continue his excessive grief—and excessive rage as well:

My abhorrence of this fiend cannot be conceived. When I thought of him I gnashed my teeth, my eyes became inflamed, and I ardently wished to extinguish that life which I had so thoughtlessly bestowed. When I reflected on his crimes and malice, my hatred and revenge burst all bounds of moderation. I would have made a pilgrimage to the highest peak of the Andes, could I when there have precipitated him to their base. I wished to see him again, that I might wreak the utmost extent of abhorrence on his head and avenge the deaths of William and Justine. (p. 79)

It is this irrational rage, I think, that he refers to as “the fiend that lurked at my heart,” and it is this (as well as fear) that prevents him from finding solace in his love for Elizabeth.

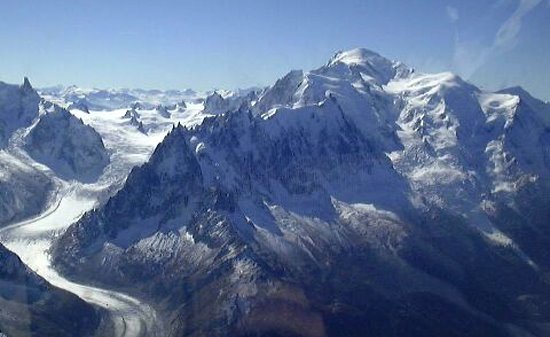

However, he does find some solace from nature—but from an aspect of nature that is rarely associated with providing solace. It isn’t the mildness of a garden or a fertile valley or a solemn, still retreat in the bosom of a forest that salves the wounds of Victor Frankenstein and calms him down long enough to lend his ear to the creature’s tale. On the contrary, he goes to the village of Chamounix, a vacation resort town on the edge of an uninhabitable land of ice and avalanche, but since he spent time there in his boyhood, it soothes him.

|

|

It also dwarfs his cares by the majestic scale of nature there, and he will mention this fact in Chapter 10. The awe-inspiring character of the landscape is what the Romantics called “the sublime.” Notice the third paragraph from the end of Chapter 9, where Victor says that the valley of Chamounix “is more wonderful and sublime, but not so beautiful and picturesque as that of Servox, through which I had just passed.”

|

|

Notice, moreover, how carefully Shelley describes the setting in terms that invite us to anticipate the encounter with the creature. Just before the passage we’ve been examining, Victor says that the beauty of the scene “was augmented and rendered sublime by the mighty Alps, whose white and shining pyramids and domes towered above all, as belonging to another earth, the habitations of another race of beings.” I seem to hear the author behind this simile saying, “Wait and you will meet the first of this new race, a being able to live here where no human being could survive—and yet it is a place made by the Father of all, a place waiting to receive its inhabitants.” Can’t you hear that in Victor’s words when he says, “The immense mountains and precipices that overhung me on every side, the sound of the river raging among the rocks, and the dashing of the waterfalls around spoke of a power mighty as Omnipotence. . . .”

|

|

He has reached, as it were, the creature’s natural home, the place where it belongs, the place waiting to receive it, where it and its descendants could be out of man’s way and content in their own activities, and what could be more appropriate than that the process of creation, started by God and continued by friends, should be taken to a new level by the intellect God conferred upon this scientist? It even seems that God has set apart this place as a home where Frankenstein’s science project may mature into a new race of intelligent beings.

This isn’t how Victor sees it, but I think this is how the author is inviting you and me to see it. She has also shown us a most unflattering portrait of the human race, which Victor is so eager to protect from the depredations of his creature. We have seen a whole society, both temporal and spiritual, condemn a woman on what amounts to mere suspicion—because she had the opportunity to do the deed and can’t explain how a trinket got into her pocket. But you and I can surely take warning from this catastrophic miscarriage of justice, hear the creature out, and then, if we must, condemn him on sound evidence, not just because he’s ugly enough to have done it and was seen a week after the murder near the spot where the boy died.